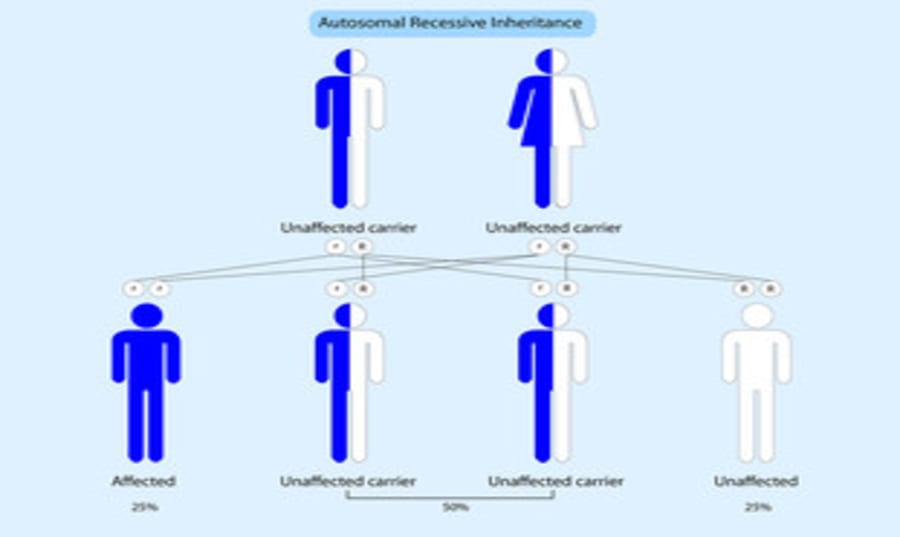

What is Autosomal Recessive Inheritance

- 2 years ago

- 0 Comments

Autosomal Recessive Inheritance:

The principal difficulty with autosomal recessive inheritance is to be sure that this is indeed the mode of inheritance in a particular family. The great majority of cases of an autosomal recessive disorder are born to healthy but heterozygous parents, with no other affected relatives. Vertical transmission, so characteristic of dominant inheritance, is rarely seen, and with the small families of the present time in many Western, industrial countries, it is unusual to see more than one (at most two) affected sibs. Thus, autosomal recessive disorders, even more than autosomal dominant disorders, usually have to be distinguished from the isolated case, with little or no genetic information to help.

Where the diagnosis makes this mode of inheritance certain, or in the minority of families where the genetic pattern is clear, risk prediction is relatively simple. In the great majority of instances, the only significant increase in risk is for sibs of the affected individual, for whom the risk is one in four. Unless the disorder is especially common or there is consanguinity, the risks for half-sibs and children, and in particular for children of healthy sibs, is only slightly increased over that for the general population.

The precise risk will depend on the frequency of heterozygotes in the population since it will be necessary for both partners to contribute the abnormal gene for a child to be affected. It is thus important to know how to estimate the chance of being a carrier for an autosomal recessive disorder, both for family members and for the general population, and this is outlined in the next section.

Risk of being a carrier:

The parents and children of a patient with an autosomal recessive disorder are obligatory carriers, while second-degree relatives (uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces, half-sibs, grandparents) will have a 50% chance of being a carrier. Each further step will reduce the risk by 50% so that it is relatively simple to estimate the chance of any relative being a carrier if their closeness to the patient is known. The risks will be higher in the presence of consanguinity, which can arise when there is an increased background degree of relatedness within a population group as well as situations when the parents are closely related as cousins, often first cousins

Sibs provide a special case: although the chance that the child of two carrier parents will be a carrier is two out of four, the chance of a healthy sib being a carrier is two out of three, because the affected category of individuals would be recognised and would be excluded from consideration. When calculating the risks for a family member being a carrier, the possibility of a new mutation can be ignored because it is excessively rare in relation to the other risks. Likewise, although the general population risk must, in theory, be added, this is usually insignificant except for the most common disorders.

Other problems with autosomal recessive disease:

Once one is confident that the mode of inheritance is indeed autosomal recessive, the difficulties in genetic counselling are much less than those encountered in autosomal dominant disorders. In particular, lack of penetrance is rarely encountered, and variation in expression within a sibship is (usually) much less. Genetic heterogeneity in either of two different senses – of multiple loci being involved, or multiple alleles at a single locus – is probably the major cause of variation within an apparently single entity. This can sometimes be recognised biochemically, as in many of the inborn errors of metabolism, while in other conditions it must be inferred from family data or be demonstrated directly by genetic testing.

X-LINKED DISORDERS:

Since virtually no serious human diseases are known to be borne on the Y chromosome, sex linkage is equivalent to X linkage, so far as genetic counselling is concerned. (An example of a disorder that can be transmitted on the Y chromosome is the Leri-Weill dysostosis caused by a mutation in the SHOX gene on the pseudoautosomal portions of the two sex chromosome short arms Microdeletions of the Y chromosome are implicated in male infertility but, except through the use of ICSI, are not usually transmitted to the next generation. X linkage produces some unusual problems that are of considerable practical importance, and as a result, X-linked disorders occupy a much more prominent place in a genetic counselling clinic than would be expected from the relative contribution of the X chromosome to the human genome.

Recognition of X-linked inheritance:

Recognition of an X-linked pedigree pattern is crucial to correct genetic counselling and is surprisingly often overlooked. The following criteria apply regardless of whether the disorder is recessive, dominant or intermediate in expression. (Note that fragile X syndrome is an exception to some of these rules.)

● The male-to-male transmission never occurs, because a man does not pass his X chromosome to his son.

● All daughters of an affected male will receive the abnormal gene, i.e. they will all carry the disorder and some may show signs or be frankly affected.

● Unaffected males never transmit the disease to descendants of either sex. A notable but so far solitary exception to this is fragile X mental retardation (FRAXA), where so-called normal transmitting (or ‘carrier’) males can carry a triplet repeat premutation.

● The risk to sons of women who are definite carriers (or affected in the case of an X-linked dominant) is one in two.

● Half the daughters of carrier women will themselves be carriers. In the case of an X-linked dominant, half the daughters of affected women will be affected and – in the general population – twice as many females as males will usually be affected.

● Fully affected females are unusual in X-linked recessive disorders but may occur (1) with a heavily skewed pattern of X inactivation, (2) in the presence of a cytogenetic anomaly, or

(3) in a ‘common’ disorder, when an affected male marries a carrier female (see later section ‘Common X-Linked Disorders’).

Leave Comment